C’è ancora tanto da scoprire sull’acne

Il termine ACNE normalmente non si può utilizzare nella pubblicità di un cosmetico in quanto per convenzione l’acne è considerata una malattia e visto che i cosmetici non possono vantare azioni o efficacia relative alla salute, di cosmetici per l’acne proprio non si può parlare. É solo un intoppo formale che le aziende cosmetiche normalmente superano utilizzando giri di parole e termini come “pelli impure” e “pelli grasse” .

Il termine ACNE normalmente non si può utilizzare nella pubblicità di un cosmetico in quanto per convenzione l’acne è considerata una malattia e visto che i cosmetici non possono vantare azioni o efficacia relative alla salute, di cosmetici per l’acne proprio non si può parlare. É solo un intoppo formale che le aziende cosmetiche normalmente superano utilizzando giri di parole e termini come “pelli impure” e “pelli grasse” .L’acne in effetti non è una specifica malattia ma una condizione della pelle collegata a molti fattori. Tra l’altro è una condizione fisiologica talmente diffusa, ne soffre circa il 10% della popolazione mondiale ma oltre l’80% degli adolescenti, che in molti casi si potrebbe classificare tra le non malattie. La sua diffusione oltre che l’impatto psicologico e sociale che può avere , specie sugli adolescenti, l’ha fatta entrare di prepotenza nel business del “selling seekness” con decine di prodotti sia cosmetici che farmaceutici disegnati appositamente per la sua cura.

L’ ACNE è classificata come un disturbo cutaneo non grave ma che richiede un intervento terapeutico per evitare che in alcuni casi si presentino lesioni che lasciano segni permanenti o che abbia conseguenze negative di natura psico-sociale. Nel tempo sono state implementate alcune linee guida per il trattamento dell’acne “medicalizzata” che comportano protocolli non senza rischi di gravi o gravissimi effetti avversi.

| La terapia antibiotica è stata accusata di aver generato ceppi batterici resistenti, la terapia con isotretinoina ha comportato centinaia di casi di malformazioni di feti, la terapia ormonale con il Diane ha portato a decessi per trombosi ecc… La valutazione del rapporto rischio-beneficio per la cura dell’acne è evidentemente complessa e difficile. |

Dopo la ricerca australiana citata in molti paesi sono stati realizzati questionari tra studenti e laureati in medicina o farmacia dove le risposte hanno ripresentato alcuni luoghi comuni, che vanno oltre i soliti errati convincimenti che circolano tra la gente comune.New concepts in acne pathogenesis

December 2013

Christos C. Zouboulis

Acne is a disease of the human sebaceous follicle [1, 2]. With a prevalence of 22-32% worldwide, acne represents the most common dermatological disease and the most common dermatological reason for medical consultation (1.1%). Around 70 to 95% of all adolescents have acne lesions [3], whereas face and upper trunk area are particularly affected. The incidence of the disease reaches a maximum at the age of 15 to 18 years. In the majority of patients there is a spontaneous regression after puberty, in 2 to 7% of them with significant scarring. In 10% of the cases, the disease persists over the 25th year of age. Not less than 15-30% of acne patients need medical treatment because of the severity or duration of the illness [4].

What causes acne?Acne treatment has to be targeted upon the clinical variants in different ages of onset and requires a good knowledge of the etiopathogenesis of the varying clinical pictures [4] (Fig. 1).

It was traditionally claimed that acne lesions develop due to an increased activity of the sebaceous glands leading to seborrhea, abnormal follicular differentiation and increased cornification as well as microbial colonization with inflammatory reaction and the subsequent immunological processes.Figure 1 - Clinical faces of acne vulgaris - From Zouboulis CC - Moderne Aspekte der Aknepathogenese Akt Dermatol

Results of recent research have significantly changed the classical view of acne pathogenesis by identifying upstream mechanisms that lead to the development of acne lesions. Androgens, skin lipids and regulatory neuropeptides appear to be involved in this multifactorial process [1, 2, 4, 5]. Hereditary factors are supposed to play an important but indirect role in the development of acne. In women, an irregular menstrual cycle and pregnancy exert an influence on the course of acne [5, 6]. In certain groups of patients, dietary factors seem to influence the disease [7]. The climate, including humidity and ultraviolet radiation, as well as other environmental factors have been accused of playing a role in some cases. Acne can also be triggered or worsened by numerous medications. The influence of psychological factors, such as stress, on the pathogenesis of acne could not be demonstrated so far, but they are supposed to influence the course of the disease [4]. Current experimental data indicate the involvement of circulating stress-associated factors (neuropeptides) in the development of inflammatory processes in the sebaceous follicle. Despite the emerging new knowledge, false claims about the pathogenesis of the disease are common not only in laymen but also in advanced medical students, as shown by an Australian study [8].

Beliefs and perceptions about acne among undergraduate medical students

Acne more than skin deep

Sconcertanti i convincimenti molto diffusi anche tra soggetti che dovrebbero essere preparati come quello che la detersione riduca l’acne o che l’acne sia contagiosa .

Acne has a genetic predisposition The positive correlation of familial incidence and severity of acne, the obligatory occurrence of acne in both homozygous twins and a conspicuous accumulation in heterozygous twins have long been known. Recent studies have shown a correlation between the acne severity grade with a history of severe acne in the parents, especially the mother [3]. However, there are interesting new insights into a direct genetic association of acne with androgen and lipid-associated disorders, such as a) the occurrence of newborn acne in babies from parents with familial hyperandrogenism, b) an association of acne with abnormal activity of the steroid 21-hydroxylase and cytochrome P 21 gene mutations, c) the assessment of identical sebum secretion rates in homozygous, but not in the heterozygous twins and d) the detection of low apolipoprotein A1 serum levels, lower content of essential fatty acids in the wax esters of sebum and low levels of epidermal acetyl ceramides in twins with acne, but not in twins without acne [9].La predisposizione genetica al momento non indica un evidente nesso causale. Si è solo notata una predisposizione genetica ma non si sa se è legata ai simili equilibri ormonali o alle analoghe composizioni del sebo.

Androgens play a major role As suggested through clinical observations, androgens play a key role in acne pathogenesis – both in the increase of sebaceous gland volume as well as in the production of sebum [10]. Gender-related genes are involved in the development of acne [9]. In addition, androgens stimulate the proliferation of keratinocytes of the ductus seboglandularis and the acroinfundibulum. Acne can develop as early as during the adrenarche [11], namely at the beginning of the increase in the synthesis of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), a precursor of testosterone, by the adrenal cortex [12]. In hyperandrogenism or hyperandrogenemia seborrhea and severe acne occur [13]. The acne-affected skin expresses higher levels of androgen receptor and higher 5α-reductase activity than the non-affected skin. Antiandrogens reduce the synthesis of sebaceous lipids and improve acne [14]. Androgen insensitive skin possesses no functional androgen receptors and neither produces sebum nor develops acne [15]. In vitro experiments with sebaceous gland-like cells of the rat and human sebocytes have shown that sebaceous lipid synthesis is upregulated in the presence of androgens and certain fatty acids, ligands of proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) (Fig. 2, 3). In fact, human sebaceous glands are equipped with both androgen receptors and with PPAR. Among the various PPAR subtypes PPARα and PPARγ are particularly involved in the regulation of lipid synthesis. The synthetic PPAR ligands thiazolidinediones and fibrates are able to increase the sebum secretion rate in diabetic patients [16]. On the other hand, a one-month topical application of linoleic acid, a PPARδ/γ ligand, resulted to almost 25% reduction of microcomedones in a clinical study [17].La relazione tra ormoni androgeni e percorsi proliferativi ed acne ha molti riscontri. Ma la iperseborrea non comporta necessariamente che si formi l’acne.

Anche se le prime manifestazioni dell’acne non sono palesemente associate a processi infiammatori, acne comedogenica, parrebbe che comunque alcuni percorsi infiammatori siano precursori anche della formazione del semplice comedone. Visto che i mediatori derivati dall’acido arachidonico possono comportarsi sia come pro-infiammatori che come anti-infiammatori, non è ancora evidente come intervenire. L’applicazione dell’acido linoleico parrebbe agire favorevolmente nonostante l’acido linoleico sia un precursore dell’arachidonico, probabilmente per la sua attività antiproliferativa e la sua interferenza con i PARR.Figure 2: Modern aspects of acne pathogenesis. Androgens, ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR), regulating neuropeptides with hormonal and non-hormonal activity and environmental factors lead to hyperseborrhoea, epithelial hyperproliferation in the ductus seboglandularis and the acroinfundibulum and expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines/cytokines that stimulate the development of comedones and inflammatory lesions [from Zouboulis CC , Eady A, Philpott M, et al. (2005) What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp Dermatol 14:143-152].

Figure 3: The triad of pathogenetic factors of acne vulgaris [from Zouboulis CC (2013) Pathophysiologie der Akne: was ist gesichert? Hautarzt 64:235-240] The in vivo inhibition of the 5-lipoxygenase product leukotriene B4, one of the strongest natural PPAR ligands, by 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors reduces the sebaceous proinflammatory fatty acids and thus the number of inflammatory acne lesions [18]. Precursors thereof, arachidonic acid and other pro-inflammatory long-chain ω-6 fatty acids stimulated both the interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-6 synthesis and the synthesis of sebaceous lipids in cultured human sebocytes. The arachidonic acid metabolism is increased in acne patients through activation of 5-lipoxygenase on affected and non-affected skin, while an additional activation of the cyclooxygenase-2 in acne lesions occurs [19]. Cyclooxygenase-2 is involved in the PPAR-regulated prostaglandin-2 synthesis in human sebocytes.

How does an acne lesion develop? A hyperproliferation of the follicular epithelium leads to the formation of microcomedones. These represent the initial acne lesion but also occur in the normal-looking skin. It is likely that the sebaceous gland of the sebaceous follicle together with the hair is subject to a cyclical process [20], which leads to a natural resolution of microcomedones [21] (Fig. 4). This early stage of development of acne lesions is associated with the activation of the vascular endothelium under the participation of inflammatory processes. This confirms the hypothesis that the very beginning of acne is an inflammatory procedure [22]. The results of Ingham et al. [23] point out in the same direction: they found bioactive IL-1 in open acne comedones in untreated patients (Fig. 5). In addition, there was no correlation between the cytokine levels and the number of follicular microorganisms.Il collegamento tra corticosteroidi, corticotropina ed acne è evidente . Il meccanismo causale che viene normalmente ricondotto agli ormoni androgeni ed a percorsi pro-infiammatori non è del tutto chiaro. La relazione tra acne e stress ( CRH e ACTH sono strettamente correlati allo stress ) è complessa, ma esistono evidenze statistiche che lo stress sia un cofattore che predispone l’insorgenza di manifestazioni acneiche con il rischio di entrare in un processo che si autoalimenta, visto che una acne grave può indurre stress per ragioni psico-sociali.Figure 4: Natural cyclic process in the sebaceous gland and development of microcomedo. Uncontrolled over-stimulation or failure of the negative feedback regulation can lead to the development of clinically significant acne lesions, such as comedones and inflammatory papules [from Zouboulis CC , Eady A, Philpott M, et al. (2005) What is the pathogenesis of acne ? Exp Dermatol 14:143-152].

Figure 5: Inflammation and sebaceous follicles. Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the sebaceous gland cells and accumulation of individual lymphocytes to the ductus seboglandularis are already detectable in healthy facial skin. In the comedones, an increased IL-1α concentration is measured, the maintenance of acroinfundibulum ex vivo with IL-1α causes a comedone-like structure with proliferation of follicular keratinocytes. P. acnes presence neither results in increased IL-1α synthesis nor in follicular epithelial changes [from Zouboulis CC (2006) Moderne Aspekte der Aknepathogenese. Akt Dermatol 32:296-302]. Interestingly, healthy sebaceous glands also express numerous cytokines, such as IL-1 and mRNA of IL-1α, IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α. Guy and colleagues [24] showed that IL-1α ex vivo induced an increased follicular keratinocyte proliferation in the infundibula of sebaceous follicles. Any over-stimulation of the pre-clinical inflammatory process or defect in the negative feedback regulation may interrupt the cyclic process of the sebaceous follicle and initiate acne lesions by inducing clinically significant follicular inflammation (Fig. 4). As mentioned previously, genetic factors cause an excess of androgen in puberty, which may cause inflammatory changes (Fig. 2). Neuroendocrine regulatory mechanisms, follicular bacteria, sebaceous pro-inflammatory lipids and food lipids as well as smoking act thereby probably as co-factors that may amplify the inflammatory processes. There is current evidence that regulatory neuropeptides (with hormonal and non-hormonal activity) can control the development of clinical inflammation in acne [25]. Numerous immunoreactive nerve fibers can be detected in the skin of acne patients that express substance P. In addition, undifferentiated sebocytes express neutral endopeptidase. Ex vivo experiments demonstrated that substance P caused a dose-dependent expression of neutral endopeptidase in the sebaceous glands. Sebaceous gland cells also express further ectopeptidases, such as dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) and aminopeptidase N (CD13), whose inhibition regulates proliferation, lipid synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines [26]. Treatment of sebocytes in vitro with IL-1β resulted in significant increase in IL-8 release. A co-incubation of the cells with α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) dose-dependently inhibited IL-8 expression. Furthermore, we could show that the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulates the synthesis of sebaceous lipids in vitro and the release of IL-6 and IL-8, and also demonstrated increased CRH expression in acne-involved skin. On the other hand, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) promotes the synthesis and release of adrenal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which can stimulate follicular inflammation. These findings point to both a central and a peripheral neuroregulation of the negative feedback mechanism of the human sebaceous gland and strengthen the hypothesis of neurogenic induction of clinical inflammation in patients with acne.

Does the Western diet cause acne? In Eskimos, the inhabitants of Okinawa Island and Chinese, acne is more commonly associated with the observed change in their dietary habits [9]. The westernized diet includes a low level of ω-3 fatty acids and antioxidant vitamins as well as higher amounts of proinflammatory ω-6 fatty acids. The ratio of ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids in the Western diet is 20:1, as opposed to a 1:1 ratio in the traditional diet schemes. Overall, the role of diet in acne still remains debatable, although in recent times the hypothesis of the role of nutrition in the development of acne has become more attractive [7, 27]. Cordain and co-workers [28] have reported that there are no acne patients in the Kitava Islanders in Papua New Guinea and the Ache hunters in Paraguay. However, the existing data do not answer the question whether this is due to genetic background or dietary habits.Visto che l’espressione di acidi ω-6 e ω-3 nel sebo è influenzata dall’apporto alimentare e visto che alcuni di questi svolgono azione antiproliferativa esiste l’ipotesi che la predisposizione all’acne possa essere influenzata dal tipo di lipidi che si assumono. Come non è per ora dimostrato che il mangiare molto cioccolato provochi l’acne, non è dimostrato che una dieta a base di pesce o con una predominanza di ω-6/ω-3 in rapporto 3/1 o 6/1 inibisca la formazione di manifestazioni acneiche.

Smoking and acne Disseminated postpubertal comedones (comedonal postadolescent acne: CPAA) were detected as a form of acne in smoking women [29] and thus the long disputed hypothesis that smoking causes acne was confirmed. A clear positive association was even detected between daily number of smoked cigarettes and acne severity grade [30]. However, other studies showed no association between smoking and acne, or even a negative relationship, where smokers remembered to have had milder acne. Studies have shown that cigarette smoke contains high amounts of arachidonic acid and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These compounds initiate a phospholipase A2-dependent signaling pathway that can further stimulate the pro-inflammatory effect of arachidonic acid. On the other hand, smokers also prefer more frequently a diet rich in saturated and low in unsaturated fats, which leads to a comparatively lower concentration of linoleic acid intake in smokers.Della relazione tra acne e fumo ho discusso qui.Non è ancora evidente quali siano i meccanismi causali anche se la presenza nel fumo di sostanze congeneri dei policiclici aromatici alogenati, evidente causa della cloracne, induce ragionevoli sospetti. L’affermazione che chi fuma assume abitualmente una dieta più ricca di grassi saturi dovrebbe essere verificata.

Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes), Toll-like receptors (TLR) and acne The cell membrane-bound TLR recognize and bind bacterial antigens. Both TLR-2 and -4 and CD14 are expressed in human monocytes and keratinocytes. The chemokine/cytokine synthesis is stimulated in keratinocytes by activation of TLR-2 via P. acnes, this activation is P. acnes subtype-dependent. These findings have revived the discussion about the involvement of P. acnes in the acne-related inflammatory process. However, P. acnes was found incapable to stimulate IL-1 release from human keratinocytes in vitro (Fig. 5). In addition, TLR-2 and -4 and CD14 are also expressed in sebocytes. The presence of P. acnes or of non-specific bacterial lipopolysaccharide antigens leads to the induction of the expression of the enzyme stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase in human sebocytes and the synthesis of the sebaceous fatty acids palmitoleate (C16: 1) and oleate (C18: 1) as well as of natural antibacterial peptides, such as human β-defensin-2, cathelicidin, psoriasin [31, 32]. This mechanism points to the role of P. acnes as a commensal bacterium that is responsible for a steady awareness of innate skin immunity against pathogenic germs. In addition, no correlation between the localization of inflammatory cells and the follicular P. acnes colonization in comedones and small papules could be detected [33] and the structure of bacterial biofilm – and not the bacteria themselves – could only be associated with acne lesions [34]. Therefore, P. acnes appears to be more involved in the latter stages of acne development and after the construction of a biofilm when it comes to significant follicular growth, and not in the initiation of acne lesions. The successful therapeutic use of antibiotics in acne is not solely due to an antibacterial activity, but can also be regarded as an expression of paraantibiotic anti-inflammatory action.Questa è la tesi più rivoluzionaria, visto che per anni la terapia elettiva dell’acne è stata basata su somministrazioni sistemiche o topiche di antibiotici e antibatterici. L’alta concentrazione di batteri propiono-acni nelle lesioni acneiche potrebbe non dimostrare che i batteri “causano” l’acne. Alcuni processi infiammatori legati alla lipolisi di alcuni lipidi sebacei sicuramente concorrono all’aggravarsi dell’acne, ma sarebbero conseguenti, in un processo che si autoalimenta dove i batteri non sarebbero la causa iniziale.

Conclusions for the clinical practice Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease to whose pathogenesis androgens, natural PPAR ligands, regulating neuropeptides and environmental factors, such as smoking and diet, are involved [35]. These factors interrupt the natural cyclic process in the sebaceous follicles and support the transition from microcomedones to comedones and inflammatory lesions. Because of this much better picture of the pathophysiology of acne, which was established by intensive research in recent years, these inducing factors should be considered by dermatologists in the planning of individual acne therapy.

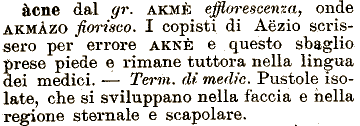

| Sull’acne c’è in realtà ancora molto da scoprire, certamente non è una specifica malattia di cui al momento si può proporre uno specifico rimedio. Molte convinzioni, anche tra professionisti, non sono supportate dall’evidenza. Che la materia sia confusa sembra quasi risultato di un suo peccato originale etimologico. Il termine verrebbe da un errore di trascrizione dal greco ACME : punto di rilievo, efflorescenza. |

pubblicato 4 gennaio 2014

References

- Zouboulis CC (2004) Acne: Sebaceous gland action. Clin Dermatol 22:360-366

- Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, et al. (2009) New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 18:821-832

- Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC (2009) Prevalence, severity and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: A community-based study. J Invest Dermatol 129:2136-2141

- Nast A, Bayerl C, Borelli C, et al. (2010) S2k-Leitlinie zur Therapie der Akne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 8 (Suppl 2):S1-S59 (Erratum and Adendum: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 8 (Suppl 2):e1-e4)

- Zouboulis CC, Eady A, Philpott M, Goldsmith LA, Orfanos C, Cunliffe WC, et al. (2005) What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp Dermatol 14:143–152

- Witchel SF, Recabarren SE, Gonzalez F, et al. (2012) Emerging concepts about prenatal genesis, aberrant metabolism and treatment paradigms in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrine 42:526-534

- Melnik BC (2012) Dietary intervention in acne: Attenuation of increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet. Dermatoendocrinol 4:20-32

- Green J. Sinclair RD (2001) Perceptions of acne vulgaris in final year medical student written examination answers. Australas J Dermatol 42:98-101

- Zouboulis CC (2010) Moderne Aspekte der Aknepathogenese. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 8 (Suppl 1):S7-S14

- Zouboulis CC (2010) Acne vulgaris – Rolle der Hormone. Hautarzt 61:107-114

- Zouboulis CC (2008) The sebaceous gland in adolescent age. Eur J Ped Dermatol 18:150-154

- Chen W, Tsai S-J, Sheu H-M, Tsai J-C, Zouboulis CC (2010) Testosterone synthesized in cultured human SZ95 sebocytes mainly derives from dehydroepiandrosterone. Exp Dermatol 19:470-472

- Marynick SP, Chakmajian ZH, McCaffree DL, Herdon JH (1983) Androgen excess in cystic acne. N Engl J Med 308:981-986

- Zouboulis CC, Rabe T (2010) Hormonelle Antiandrogene in der Aknetherapie. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 8 (Suppl 1):S60-S74

- Imperato-McGinley J, Gautier T, Cai LQ, Yee B, Epstein J, Pochi P (1993) The androgen control of sebum production. Studies of subjects with dihydrotestosterone deficiency and complete androgen insensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 76:524-528

- Trivedi NR, Cong Z, Nelson AM, et al. (2006) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors increase human sebum production. J Invest Dermatol 126:2002–2009.

- Letawe C, Boone M, Pierard GE (1998) Digital image analysis of the effect of topically applied linoleic acid on acne microcomedones. Clin Exp Dermatol 23:56-58

- Zouboulis CC (2009) Zileuton, a new efficient and safe systemic anti-acne drug. Dermatoendocrinol 1:188-192

- Alestas T, Ganceviciene R, Fimmel S, Müller-Decker K, Zouboulis CC (2006) Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of leukotriene B4 and prostaglandin E2 are active in sebaceous glands. J Mol Med 84:75-87

- Xu Y, Yang L, Yang T, Xiang M, Huang E, Lian X (2008) Expression pattern of cyclooxygenase-2 in normal rat epidermis and pilosebaceous unit during hair cycle. Acta Histochem Cytochem 41:157-163

- Cunliffe WJ, Holland DB, Clark SM, Stables GI (2000) Comedogenesis: some new aetiological, clinical and therapeutic strategies. Br J Dermatol 142:1084-1091

- Zouboulis CC (2001) Is acne vulgaris a genuine inflammatory disease? Dermatology 203:277-279

- Ingham E, Eady EA, Goodwin CE, Cove JH, Cunliffe WJ (1992) Pro-inflammatory levels of interleukin-1 alpha-like bioactivity are present in the majority of open comedones in acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 98:895-901

- Guy R, Green M, Kealey T (1996) Modeling of acne in vitro. J Invest Dermatol 106:176-182

- Zouboulis CC (2009) Acne vulgaris and rosacea. In: Granstein RD, Luger T (eds) Neuroimmunology of the Skin – Basic Science to Clinical Practice. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 219-232

- Thielitz A, Reinhold D, Vetter R, et al. (2007) Inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DP IV, CD26) and aminopeptidase N (APN, CD13) target major pathogenetic steps in acne initiation. J Invest Dermatol 127:1042-1051

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. (2008) Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol 58:787-793

- Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Bordignon V, et al. (2010) Underestimated clinical features of post adolescent acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 63:782-788

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol 2002; 138:1584-1590.

- Schäfer T, Nienhaus A, Vieluf D, Berger J, Ring J (2001) Epidemiology of acne in the general population: the risk of smoking. Brit J Dermatol 145:100-104

- Nakatsuji T, Kao MC, Zhang L, Zouboulis CC, Gallo RL, Huang C-M (2010) Sebum free fatty acids enhance the innate immune defense of human sebocytes by upregulating β-defensin-2 expression. J Invest Dermatol 130:985-994

- Zouboulis CC (2009) Propionibacterium acnes and sebaceous lipogenesis: A love-hate relationship? J Invest Dermatol 129:2093-2096

- Alexeyev O, Lundskog B, Ganceviciene R, et al. (2012) Pattern of tissue invasion by Propionibacterium acnes in acne vulgaris. J Derm Sci 67:63-66

- Jahns AC, Lundskog B, Ganceviciene R, et al. (2012) An increased incidence of Propionibacterium acnes biofilms in acne vulgaris: a case control study. Br J Dermatol 167:50-58

- Zouboulis CC (2013) Pathophysiologie der Akne: was ist gesichert? Hautarzt 64:235-240

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento